John Mulaney to Die on Live TV

Morbidity, Absurdity, and the Extremism of Final Form Internet Brain Rot

Aaron Bushnell was worth more dead than alive.

“This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal,” he announced live on Twitch, before renouncing his complicity in the Gazan genocide, lighting himself ablaze, then shouting his final words: “Free Palestine! Free Palestine! Free Palestine!”

Self-immolation is not a novel form of political protest, but freely and easily broadcasting it live to billions of smartphones is a new phenomenon. The 25-year-old Massachusetts native—who was neither depressed nor distraught—reasonably calculated that the goal of stopping genocide would simply be better served by the tragic spectacle of his own death than by anything else he might do alive.

Aaron Bushnell was angry, but he wasn’t crazy. Howard Beale, on the other hand, was a good bit of both—which made for a delicious double entendre when he galvanized fictional and real audiences alike with the clarion call from 1976’s Oscar-winning Network: “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore.” The newscaster was depressed when he first declared his intention to kill himself on live TV. By the time the network executed him, he was full of life—but executives had determined he was worth more to the corporation dead than alive.

Before coming to his untimely end, Beale rallied his millions of followers to help tackle moral decay and international corporate corruption. A Middle Eastern power had angled to take over a central organ of American public influence, an outrage that would have resonated with Aaron Bushnell if he ever watched the film. Bushnell and Beale both paid the ultimate price for repudiating an immoral elite; only Bushnell in his dignity chose death whereas the fictional Beale did not.

Sixteen days after Bushnell’s act of extreme protest, John Mulaney Presents: Everybody’s in L.A. debuted on Netflix. I have written previously about this ineffably absurdist talk show here and here, and as such had no intention to cover the show yet again. But as the second season has unfolded in unsettling—indeed, existential—terms leading up to its finale, I cannot escape the conclusion that John Mulaney is going to join Bushnell and Beale and kill himself live on TV on May 28, 2025.

This show—this entire creative endeavor—is one despondent man’s elaborate attempt to wrestle with the despair and mental illness borne from a life lived thoroughly enmeshed in modern society.

I hope I am wrong. A dead John Mulaney would be a huge loss, and besides—every single person should live a long and happy life. But if I’m right, I feel obliged to inform you of this potential episode of TV history so you can experience it live. Even more importantly, I need to understand why someone like John Mulaney might go all the way to his very end out of sheer, uncompromising commitment to the bit.

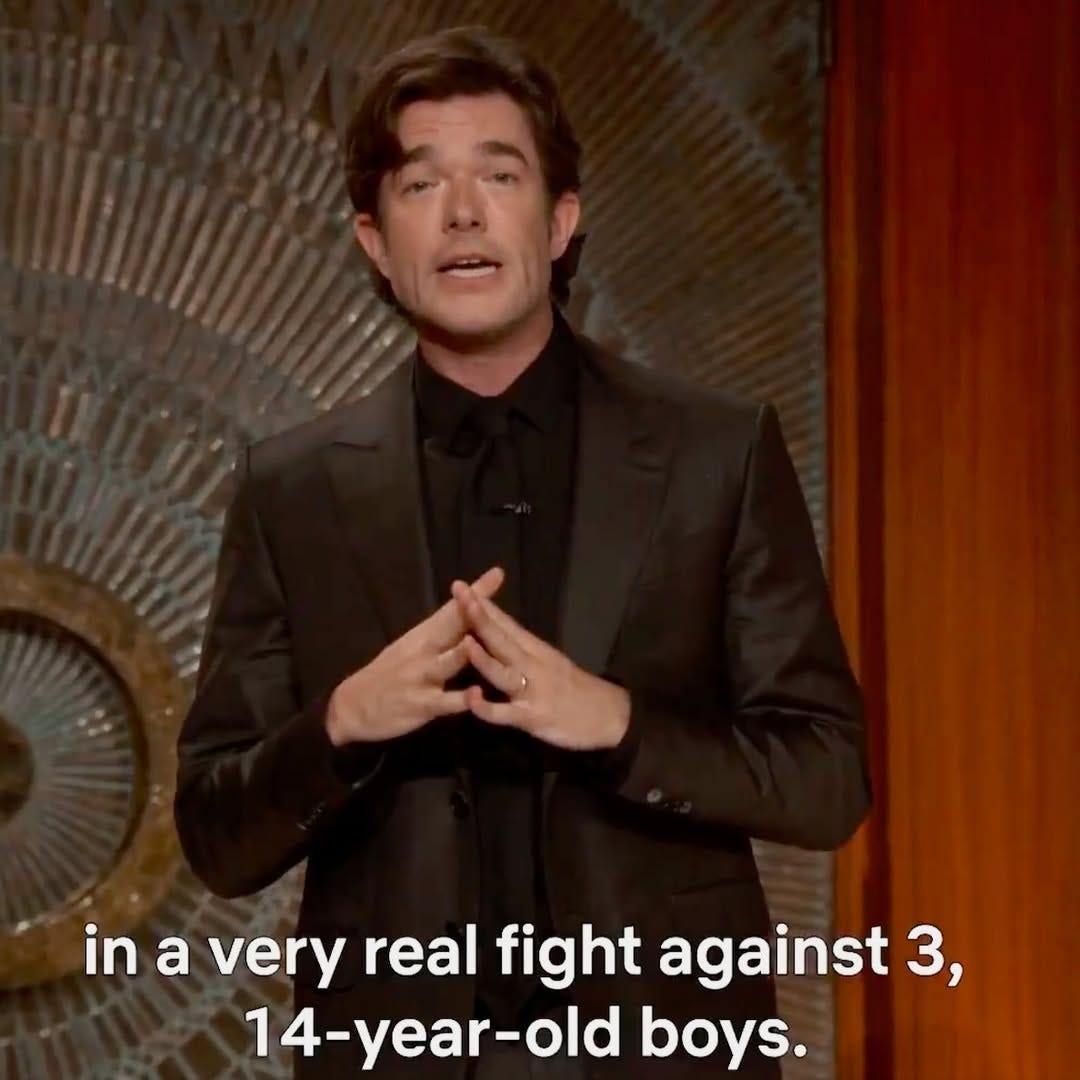

How the hell did we get here? This potentially fatal saga began in 2020, when a Reddit user named u/probablycashed posed the bizarre hypothetical of 100 unarmed men fighting a single silverback gorilla. Last month, popular YouTuber MrBeast brought the thought experiment forth from deep internet latency, and it has since gone viral. Then on the April 30th episode of Mulaney’s show, he shared his writing team’s decision to actually pursue a variation of the concept: At the May 28 season finale (7pm PST / 10pm EST) the 42-year-old will endeavor to fight three 14-year-old boys.

Let’s be clear: the wrong 14-year-old on the wrong day could easily kill Mulaney in a fight. With each additional 14-year-old the possibility of severe injury or even death only increases exponentially. Maybe he will wear padded headgear during the bout. There could be some sort of referee to keep things from getting out of hand. Perhaps this is all a ruse, with the “fight” revealed to be a sequence of one-on-three non-combat challenges like chess and a pie-eating contest.

Truly anything is possible on this show, but if in the end an honest-to-god MMA-style fight between Mulaney and three 14-year-old boys results in one or more of them brutally mangled—or worse—we shouldn’t be surprised. Looking back at this season, the signs have been there all along.

A pre-taped Willy Loman Focus Group peaks as the emotional and artistic zenith of the season premier. Mulaney brings eleven different actors into character, with the “focus group” climaxing in a collective rendition of the Death of a Salesman “there were promises made” speech. The performance is discordant to the point of comic unintelligibility. As viewers we are expected to either know the substance of the speech, intuit its meaning, or simply not care as we delight in the creativity of the skit.

But while the Willy Lomans perform in disjointed union, the camera pans back to Mulaney, the stage dad passionately pontificating along in silent solidarity. This is a skit about him; he is the man worth more dead than alive. We arrive at the thesis of this season: this show—this entire creative endeavor—is one despondent man’s elaborate attempt to wrestle with the despair and mental illness borne from a life lived thoroughly enmeshed in modern society.

Like any recovering addict, John Mulaney must navigate the daily abyss of human existence without the artificial numbing he once relied on. Sometimes a substance-free lifestyle leaps out of the subtext, like when musical guest Bartees Strange performs a song named Sober from his new album in episode five. The prison of severe chemical dependency is dark, but escaping into the light of day and feeling the fullness of life can at times lead to an even bleaker place.

It’s all the more troubling given how consistently Mulaney muses on fatherhood throughout the season. We learn about potty training and tender toddler morality, but we also witness a star relating to his creative team—writers, producers, and even his elder statesman sidekick Richard Kind—with a loving and admiring paternalism. One bit leans all the way into the premise, complete with a baby monitor into the writers’ room so Mulaney can make sure his “kids” sleep through the night.

These are the heirs who will benefit from Mulaney’s spectacle of self-sacrifice, not his comfortably wealthy biological family. In the Arthur Miller play, Loman commits suicide to try and provide his sons with a shot at the American dream he couldn’t achieve. For Mulaney, everyone involved on the creative team will graduate from the show with a mythic achievement to their name—a priceless calling card in an era where the old Hollywood dream is accessible to only a shrinking few.

By taking absurdity to its logical conclusion, Mulaney would be forcing us to confront our casual relationship with reality, our normalization of the extreme, and our inability to distinguish between sincere and ironic discourse.

Now in his forties, Mulaney regularly riffs on his ailments and physical fragility. A full episode is dedicated to the question of whether to undergo major surgery for a lifelong hip problem. Another episode revels in recounting bladder issues and a recent prostate exam. Mulaney plays it all for laughs, but beneath the monologue rests a sober awareness of profound vulnerability.

Mulaney showers the notoriously self-destructive Johnny Knoxville with more enthusiastic praise than he can summon for guests like Jimmy Kimmel, David Letterman, Conan O’Brien, Jerry Seinfeld and Jon Stewart. Profuse recognition is reserved not for these icons, but for an entertainer who built his career on injurious and potentially fatal stunts.

The third episode embraces death head on, with a dedicated focus on the subject of funeral planning and a taped recording of Mulaney’s last will and testament. But not every episode touches so explicitly on mortality. At times we endure the former SNL star suffering the rigamarole of adult life that kills his spirit, from endless lines at the DMV to strategizing for tax season.

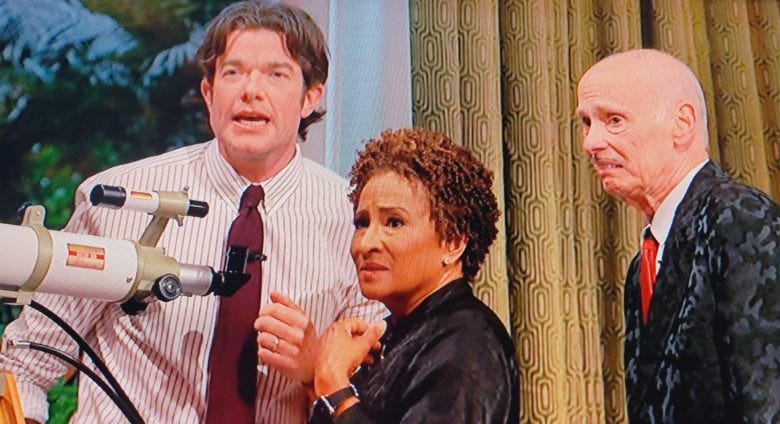

The show establishes a detached and even casual relationship with violence. In a recurring bit we peep at the studio’s neighbors through a telescope, only to witness the same vicious assault unfold in every apartment at once. Weary of paperwork and days spent testifying in court, Mulaney brushes empathy and societal duty aside and declines to intervene.

From the sanctum of its made-for-TV living room, the show peers out into a chaotic world at war with itself. But inside the studio, a stream of copycats and doppelgängers evoke a celebrity self that is unstable, replaceable, and ultimately doomed. In episode 9 Andy Samberg reveals he is just a character stolen from a “real” Andy Samberg, who berates the faux Sandberg’s performance from the audience. We discover that Mulaney, and all celebrities, are but replicas of “real” people whose identities they assume—with or without consent.

In the previous episode, the same telescope that reveals society’s collapse also shows an uncanny replica of the Seinfeld apartment, but instead of the show’s four famous leads their characters and bodies have been assumed by the four members of the jam band Phish. Nothing is real; everyone can and will be substituted by someone else.

It doesn’t stop where celebrity ends. In the traditional late-night format, the straight man announcer stands in for the audience—reacting to the zany host and keeping us rooted in a reliable perspective. But in Everybody’s Live, announcer Richard Kind is the most unhinged of all. We identify with him by convention, but as he embodies entirely different personas in each episode we are forced to confront our own fractured and inconsistent personalities. If Mulaney is “performing” a real and knowable person named John Mulaney, for Richard Kind—and for us—a single anchor personality may not even exist at all.

Experiencing this season of Everybody’s Live feels like a carefully calibrated Charlie Kaufmann narrative: unreal and increasingly unstable. The collective madness required of all participants—from host to guest to audience—throws into question the reliability and the sustainability of not just the show but the larger moment from which it emerges.

It’s Mulaney’s unhinged world; we’re just living in it. This ambitious show need not end with the cliché of Mulaney waking up from a deep slumber, relieved to find that it was all just one long fever dream. But the show must come to an end—and not because all good things come to an end, but because it’s totally insane.

Death by three fourteen-year-olds would spell violence for the sake of authenticity, in the name of outdoing the insanity of the internet and exposing final form internet brain rot for its deeply dangerous implications.

We identify with announcer Richard Kind by convention, but as he embodies entirely different personas in each episode we are forced to confront our own fractured and inconsistent personalities. If Mulaney is “performing” a real and knowable person named John Mulaney, for Kind—and for us—a single anchor personality may not even exist at all.

With Howard Beale and Aaron Bushnell, death was pursued as a protest against the powerful—a rage against the machine. As a United State Air Force cybersecurity-trained engineer, Bushnell was acutely aware of the American role in Gaza—and his exact contribution to it. But the decision to end his life on a Twitch livestream was much more than a desperate way out of the military industrial complex. He did it to raise our awareness and shock our collective conscience from complacency.

It is even truer now in 2025 than it was in 1976: our media ecosystem requires ever more extreme gestures to convey meaning, and we struggle to value life outside its potential as content. Mulaney isn’t angry or outraged; he’s neither bitter nor aggrieved. For Mulaney to release us all from the vice grip of Everybody’s Live, his death would be the ultimate farcical act. It would be the stuff of legends.

By taking absurdity to its logical conclusion, Mulaney would be forcing us to confront our casual relationship with reality, our normalization of the extreme, and our inability to distinguish between sincere and ironic discourse.

One hundred unarmed men fighting a single silverback gorilla is deeply unserious—until we choose to take it seriously. In doing so, even in a dramatically downscaled version, Mulaney and his team are mocking us and the internet culture now driving mainstream society off a cliff. They’re calling our bluff. They’re exposing the blurred and artificial world where we now live our lives.

When we take this challenge to its extreme conclusion, everybody’s dead. With John Mulaney.

ICYMI, check out these related posts:

In Case of Emergency, Break Glass. Literally.

The term 'five-alarm fire' has returned to our lexicon for terrifying reasons. While Southern California still bears the scars of recent wildfires, our nation's capital faces a different kind of inferno: the systematic dismantling of democratic institutions by Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

Kibitz Room Confidential

“The greatest loss of them all” is first and foremost personal, the loss of innocence and raw vitality that fades with age. It’s also a cultural death, embodied by the centrality of livestreams and the decrepitude of the once great Kanye West. The greatest loss is planetary collapse, in which the only silver lining comes as a poetic prophecy from Bowie’s Life on Mars.

And no one hits the silver line like Lana Del Ray.

Pritzker's Billions

“Seriously Evan,” you’re saying as you read this, “we all know that as recently as December the BET+ network released Brewster’s Millions: Christmas, a generational sequel to the 1985 comedy starring Richard Pryor and John Candy. The last thing we need is another installment of Brewster content.” And yet we do.

“Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people.” Eleanor Roosevelt

omg