A weekly cultural and political brief—Certain Sips: the Weekend Brew

I spent most of my twenties lost, searching for meaning, unmoored and entirely unmotivated.

It sounds cliché, but it’s true. For a time, I grasped at a semblance of purpose left over from my undergraduate studies and tagged along as friends shot their first music videos and feature films. Production was never going to be my career path, but in that lost season of delayed adolescence it gave me something to be a part of, something to do.

Still, I spent more time on set getting high and scrolling Twitter than substantially helping with production efforts. I had nothing better to do, so in the fall of 2010 I joined my old friend Stephen and his team up north, staying at his family’s cabin while they filmed Marvin, Seth and Stanley.

Between one-hitters of Orange Trainwreck, which was the sativa-dominant strain at the time, I approached local vendors begging them to “sponsor” a meal for the cast and crew. And when that fell through, I found increasingly creative ways to repurpose leftovers into soups and sandwiches for the team.

In retrospect, it was a pretty miserable moment within an overarchingly sorry phase of my life. Soon enough I would find direction, reach higher, and begin contributing to society in meaningful ways. But that autumn in Brainerd, Minnesota (a few soups and sandwiches notwithstanding), I wasn’t yet in a position to produce much of anything—but I was hell of a consumer.

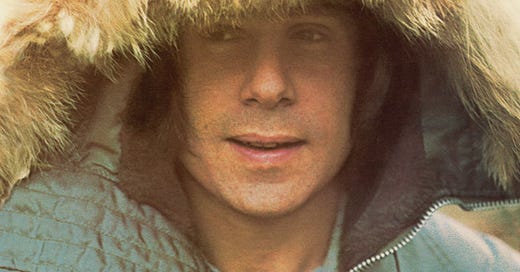

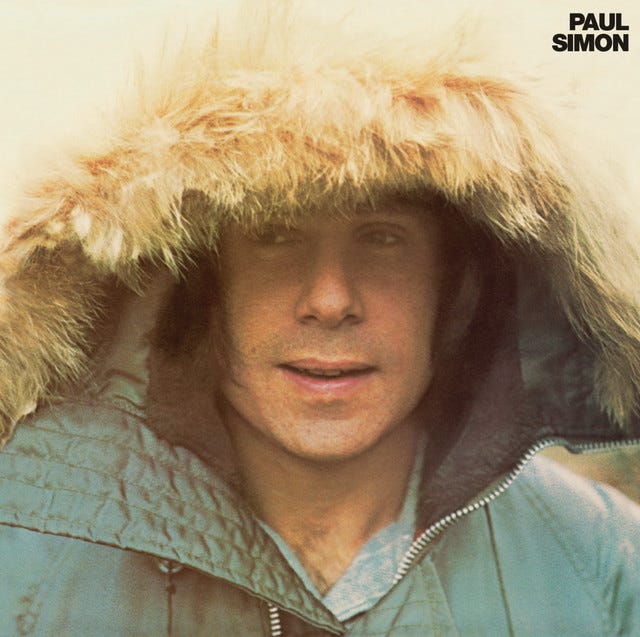

I took meal breaks and snack breaks, smoked tons of weed, and listened to hours upon hours of music. As you know I’m a huge Simon & Garfunkel fan, but I haven’t always been hip to the artists’ solo works. While I was wasting away on the Marvin, Seth and Stanley production, Stephen introduced me to two Paul Simon songs off the singer-songwriter’s second self-titled album released in 1972: Duncan and Peace Like a River.

Good Listening

Duncan hit twenty-five-year-old, aimless me like a ton of bricks. This soulful ballad recounts a young man setting out from his dead-end small town, running on empty, and ultimately finding meaning in his first intimate experience. There is a flute section, and it’s magnificent.

Even as I’ve aged out of the life stage so hauntingly evoked in Duncan, its soul-penetrating power has yet to be diluted. Hundreds of listens later, both of these songs still hit the same as the first time I heard them. While Duncan romanticizes both the danger and the freedom of venturing out independently from home, Peace Like a River spins a collective tale of liberation found in the mass movements that revere a city as a sacred safe haven.

More Good Listening

Peace Like a River anchors the back side of the album, and it ends the same way Duncan begins on the front side: our protagonist is awake before dawn, unable to get back to sleep any time soon. In Duncan, the loudly copulating couple in the motel room next door intensifies late adolescent feelings of isolation. By the time he’s awoken at 4am in Peace Like a River, the intimacy is now coming from inside the room: “We sat starry-eyed. Oh, we were satisfied.”

From the opening of the album to its close, Simon grows from a lost and lonely kid into a young adult in communion with lovers, intimately connected to a city and peacefully rooted in nonviolent revolution. These days, peaceful protest is on more minds than at any other time I can remember. Personally I am grateful to live a much more fulfilling life than that of my twenties; yet as a result I now have much more to lose.

“You can beat us with wires, you can beat us with chains,” Simon sings in Peace Like a River, “You can run out your rules, but you know you can’t outrun the history train.” Whatever this means, it sure sounds good right now. It’s a soothing thought. “I’ve seen a glorious day,” he croons.

From your mouth to god’s ear, old sport. From your mouth to god’s ear.

ICYMI, check out these related posts:

A Single Day in '64

I put Bleecker Street on heavy rotation last year as it is remarkably catchy. Hypnotic, even. Paul Simon’s lyrics evoke ritual, loneliness, human connection and the lack thereof. The downtrodden, a recurring emotional motif of the Simon and Garfunkel cinematic universe, are held in the tender cradle of cheap apartments and sad cafes. This is a deeply spiritual song. It is deeply faithful. Bleecker Street is, in fact, a prayer.

Goonies Never Say Die

Here Cindy Lauper is in her zone, wildly emotive in a way that adults just can’t access. The song’s climactic nonverbal expression of raw emotion — “yeah yea yea yea yeyeah” — hits when a deep feeling transcends even lyrics. Consider, as another example, the haunting “li la li” chorus of Simon and Garfunkel’s heartbreaking anthem The Boxer.

Well done, Evan. I too am a diehard Paul Simon fan. Have been since long ago. You’ve done an excellent job of bringing forth the value of his music. Way back when, I wrote a really excellent thesis paper on why Paul Simon should be named Poet Laureate of the United States. A relatively easy paper to write, since the voluminous amount of great poetry from this artist was easily accessible and made for a great opinionated copy and material. Handed it in with the confidence of knowing that I did a kickass job on the paper. Got it back the following week with an F. To say the least, I was pissed as a dog in a hard fight. Met with my professor, asked why he failed the paper. His curt answer was the thesis topic was absurd. I told him it was the first F that I’d ever received on a paper, and I wasn’t happy about that. Brokenhearted to say the least. He re-graded it and gave me a D-. Hell of a guy. Love Paul Simon. Love your essay.

Good tunes